The Villchur Blog posts articles about the life and career of author, educator, and inventor Edgar Villchur. This is the second of three articles about Villchur’s experiences in World War II.

Edgar Villchur spent four years in the Army Air Corps during World War II—two years in various training camps in the US, and twenty-eight months in the South Pacific. Villchur’s unit was the 340th Fighter Squadron, part of the 348th Fighter Group. They arrived in Port Moresby, New Guinea on June 23, 1943, set up camp, and remained there for six months. Over the next two years of his service, the group moved many times, from New Guinea north to the Philippines, and finally to Ie Shima, part of Okinawa. They spent two to three months in each new camp. With each move, the 348th Fighter Group moved closer and closer to Japan.

At each location, the unit had to clear the jungle, erect canvas tents, build wooden floors for those tents, build an airstrip for the twenty-five P-47s and P-51s, and establish good relationships with the native people. Life in the jungle meant dealing with iguanas and monkeys wandering around camp. Mosquitoes were everywhere, carrying malaria and other diseases. Soldiers slept with mosquito netting around their cots. Villchur remembered the sound of the mosquitoes buzzing against the netting, trying to get in. If your arm brushed against the netting by mistake, the bugs would bite you even through the netting, and you would wake up with large welts.

More soldiers were killed by disease than by combat in World War II. Troops in the Pacific battled malaria, beriberi, and dysentery. In the jungle it was nearly impossible to maintain clean, let alone sanitary, conditions. Villchur was one of thousands of US soldiers who contracted hepatitis in 1943. He spent more than a week in the infirmary, and another two weeks recovering in his tent.

Ironically, it was later discovered that the vaccine the army had administered to all its troops against yellow fever had the side effect of causing jaundice and hepatitis in as many as fifteen percent of those vaccinated. Few soldiers died of this hepatitis, but it kept them from performing their regular duties for weeks at a time.

Villchur remembered an incident where a superior officer came into the infirmary to visit the troops. Those who could stand got out of bed, stood at attention, and saluted. Villchur’s nurse urged him to stand up, but he was too weak. The superior officer said it would be fine for him to come to attention while lying in bed. Villchur saluted the officer from the bed, and released his salute once it had been acknowledged by the officer.

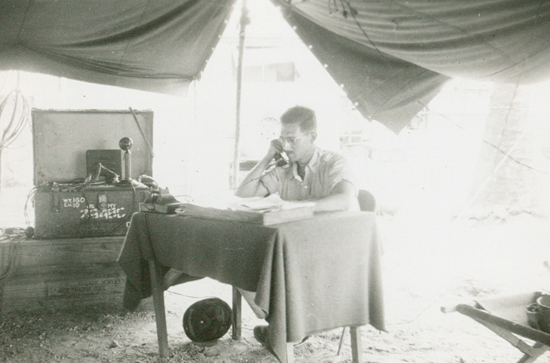

Because he had completed Officers’ Candidate School before shipping out, Villchur arrived overseas as a Second Lieutenant, and was promoted to First Lieutenant on March 19, 1943, and to Captain on June 27, 1945. His principal duty was Group Communications Officer of the 348th fighter Group. On March 21, 1945, he was given the additional duties of Cryptographic Security Officer and IFF (Identification Friend or Foe) Officer.

Villchur’s tent mates, all officers, were Arthur Schrager, Joel Pitchford, and Noble D. Jones (“Jonesy”). The four tent mates became close friends. They lived and worked together, and shared a slit trench, or fox hole, during air raids. Villchur remembered the distant whine of Japanese airplanes that meant the camp was under attack. He said it reminded him of the drone of the mosquitoes.

Soon after hearing the planes, the air raid alarm would go off, but most of the GIs had already awakened (if it was nighttime, which it usually was), put on their helmets and shoes, run out of their tents, and jumped into the fox holes. They would all be accounted for except for Jonesy, who invariably arrived, groggily putting on his helmet, just seconds before the first bomb hit. Fortunately, air raids were becoming less frequent by the time Villchur’s unit arrived in 1943, since the Allied forces had turned the corner in the war, and the Japanese were retreating.

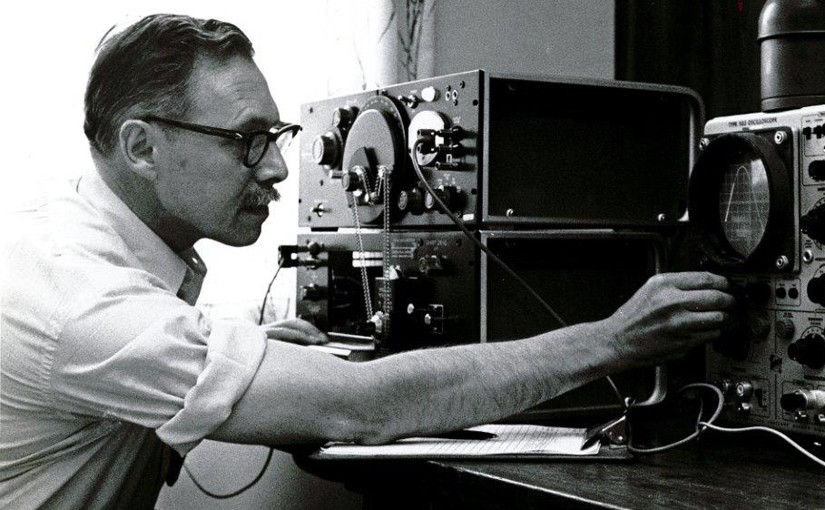

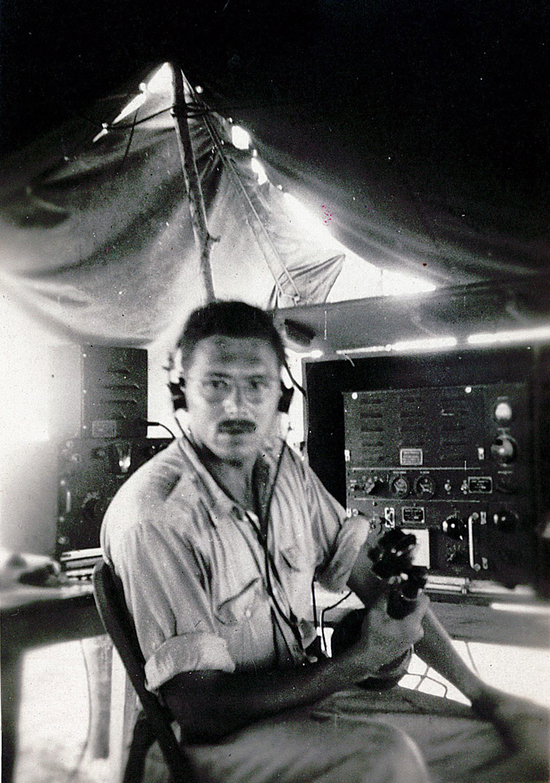

Villchur’s main occupation was repairing and maintaining the radio equipment on the ground and in the airplanes Clear, intelligible radio reception was of the utmost importance in the air war in the Pacific. Fighter pilots needed to communicate with each other about enemy aircraft, about anti-aircraft weapons on the land or sea below them, and about the details of their missions. It was also absolutely essential for the pilots to have good communications with base camp.

Villchur told a story of a time when a DC-2 (a plane that carried fourteen passengers with two to three crewmen) approached the airfield without radio contact. The ground radio operator tried again and again to raise the pilot, but there was no answer. None of their planes were expected in, so the approaching plane was highly suspicious. The commanding officer gave the order, and the plane was shot out of the sky. On inspection, it was discovered to be a captured American airplane with a crew of enemy soldiers who had been attempting to attack the camp.

Everyone on base understood the implications of that incident: if an American pilot tried to land without a functioning radio, he was in danger of being shot by friendly fire. Villchur took his job very seriously, and kept the radios on the twenty-five P-47s in his squadron in top working order. He went further, figuring out problems with faulty equipment, recommending changes in Army procedures to correct those problems, and writing up procedures for testing and maintaining the radios on the ground and in the air.

Despite the fact that they were camped in a combat zone, much of their time was taken up with the ordinary activities of daily living—camp maintenance, eating in the mess tent, playing poker (Villchur became a skilled poker player, and was part of a regular game later in life). The soldiers hired indigenous people to clean their tents and do their laundry. One young man from Papua, New Guinea beat Captain Schrager at checkers, to the captain’s great surprise and dismay.

One of Edgar Villchur’s favorite stories of his time overseas demonstrated his inventiveness as well as his esprit de corps. He found out that coke syrup was available from the commissary. Using spare parts, he devised a compressor, added a stainless steel tank and a spigot, and created a machine that dispensed cold Coca Cola. The soldiers could get a cold cup of Coke anytime. It was a welcome reminder of home.

Villchur had a jeep that he named Rosemary after his girlfriend (and later wife) back home. Using his skill with the paintbrush, he decorated his jeep with her name in elegant Trajan lettering, his favorite font. When he started Acoustic Research many years later, he used that same font to create the AR logo.

One night in the camp a soldier cried out, probably from a nightmare. Villchur got up and cocked his 45, and heard the sound of 45s being cocked all around the camp. The soldier had fallen out of bed and gotten tangled in his mosquito netting. No harm was done, but it served as a reminder to all that they were in a combat zone, and that they had to be on guard at every moment.

When Villchur started his military training, he tried to become a weatherman, but was assigned to radio technician school. Many years later, Villchur said “The army, in its infinite wisdom, put me in engineering.” His sarcastic comment was meant to convey his contempt for the army’s habit of asking enlistees for their opinions and then ignoring those opinions. But the Army Air Corps’s decision to give Edgar Villchur an education in engineering allowed him to go on to make major contributions to the fields of both sound reproduction and hearing aid design.