In the early part of the twentieth century, Edgar Villchur’s father, Mark Efimovitch Villchur, was working as the City Editor of the Russkoye Slovo, the largest of the three Russian-language daily newspapers in New York City. He had two major letters to the editor (we would call them Op-Eds today) published in the New York Times. His beloved wife, Mariam Vinograd Villchur, was a biochemist at the Rockefeller Institute, and had four scientific articles published in chemistry journals. The family was living in Manhattan, and life was good.

Tragedy struck the family when Mariam died at the age of thirty-four in the worldwide flu epidemic that followed World War I. Mark was able to continue to work full-time because of child care help from relatives in New York and Connecticut.

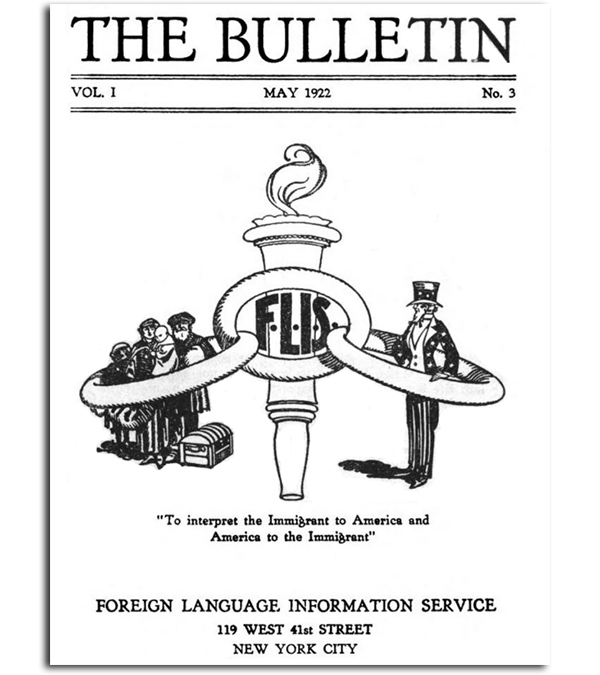

In 1922, Mark took a job as the manager of the Russian language bureau at the Foreign Language Information Service. The FLIS was initiated in 1918 by the US Committee on Public Information, a campaign by the federal government to convince Americans to support the country’s entry into World War I. The organization was given the auxiliary task of explaining American life and institutions to immigrants in their own languages. For more than two decades after its founding, FLIS sent weekly educational articles in nineteen languages to nine hundred foreign-language publications in the United States. It assisted hundreds of thousands in the process of becoming citizens, and helped immigrants learn about American industries, farming, and other career paths. In one informational pamphlet, the work of the FLIS is described: “It has served as a national ‘information desk’ for newcomers in every state, helping to solve the difficulties faced in a strange country, to unite families, to encourage naturalization…. It has opposed unjust anti-alien bills and urged legislation to facilitate citizenship and fair play…. It has fostered interest in the folk arts, and encouraged the foreign born to preserve and contribute the best of their native culture to American life.”

Although the US Committee on Public Information was disbanded after World War I, the FLIS continued its work, and in 1940 changed its name to the Common Council for American Unity. The enormous waves of immigration were over, but first- and second-generation immigrants still faced problems of assimilation, discrimination, and loss of their ethnic identities. The CCAU broadened its mission to helping to create unity, mutual understanding, appreciation, and acceptance for the various communities of foreign-born Americans.

Read Lewis, the director of the FLIS (and Mark Villchur’s boss), is perhaps best known for his 1939 book How to Become a Citizen of the United States. He became the Director of the CCAU, and went on to publish its magazine, Common Ground. Contributors to this legendary literary quarterly included Archibald MacLeish, William Saroyan, Eleanor Roosevelt, Paul Robeson, Woody Guthrie, Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Alan Lomax, and Arthur M. Schlesinger, Sr.

It should be noted that the artist Yasuo Kuniyoshi, the first living artist chosen to have a retrospective exhibit at the Whitney Museum of American Art, lived for many years in Woodstock, New York, and taught at the Art Students’ League there. He died in 1953 at the age of sixty-three, so Edgar, who got to Woodstock in 1952, never met him, but Kuniyoshi’s widow, Sara Mazo Kuniyoshi, was a member of the Woodstock artist community for many years after that, and was a friend of my parents, Edgar and Rosemary Villchur.

Read Lewis gathered some of the great progressive minds of the era to be part of the Common Council for American Unity. The Board of Directors included several “muckraking” journalists: Ida Tarbell, author of The History of the Standard Oil Company; William Henry Irwin, whose most famous articles covered the San Francisco earthquake and anti-Japanese racism; and Mary Phillips Riis, social reformer and the widow of Jacob Riis (photographer and author of How the Other Half Lives. Also on the board were the US Commissioner of Immigration and Naturalization, James Houghteling; Slovenian author, advocate for ethnic diversity, and Common Ground’s first editor Louis Adamic; child-labor activist Josephine Roche; journalist, reformer, and Manhattan Borough President (1910-1913) George McAneny; and future U.S. senator Alan Cranston, who both wrote for and later edited Common Ground.

The Advisory Board was chaired by John Palmer Gavit, a famed journalist and the author of the first style guide for newspaper reporters. Other members of the board included suffragist Carrie Chapman Catt, founder of the League of Women Voters; Norman Thomas, pacifist and presidential candidate (on the Socialist party ticket); Julia Lathrop, advocate for child welfare and Commissioner of the United States Children’s Bureau (1912-1921); and Dr. James T. Shotwell,, a member of President Woodrow Wilson’s foreign policy advisory group.

James Shotwell was a professor of history at Columbia University and a renowned scholar. He contributed two hundred fifty articles to the Encyclopedia Britannica. President Woodrow Wilson appointed him official historian of the United States delegation to the Paris Peace Conference of 1919, for which he wrote the provisions establishing the International Labor Organization (ILO). He promoted a policy of internationalism, first with the League of Nations and later, when the League foundered, with the United Nations. He is considered one of the main parties (along with Eleanor Roosevelt) responsible for the inclusion of the Declaration of Human Rights in the UN Charter. He was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize in 1952.

It is almost certain that Mark Villchur, an executive staff member of the CCAU, would have met and conversed with Dr. Shotwell, a member of the group’s advisory board.

In 1911, Dr. Shotwell purchased land on Overlook Mountain in Woodstock, and built a house in the Craftsman style for himself and his family. Decades later, Mark Villchur’s son Edgar would buy that same house from the Shotwell family and live there for more than fifty years.

I had never heard the story of this connection, and assumed that my father had never learned of it. As I was writing this blog post, however, I came upon a folder labeled “Read Lewis” among my father’s files. Inside was a letter from a colleague of Lewis’s, advising friends and family of his death, and a letter my father had written in response. Edgar Villchur wrote: “My father worked for the old Foreign Language Information Service, first as head of the Russian Bureau. I knew Mr. Lewis in the late twenties, when as a child I visited the office. About fifteen years ago [the letter is dated April 6, 1984] I received a phone call from Read Lewis. The bus had dropped him off at Woodstock for one of his hikes. He refused my offer to pick him up with my car, and when I started to give him walking directions he said ‘I know your house well—I used to visit the Shotwells there in 1914.’ We spent a very pleasant afternoon at my house.”

I was delighted to learn that my father did indeed know of the connection and of the amazing coincidence that he had purchased the home of Dr. Shotwell, who worked alongside his own father on the important issues of helping immigrants and fostering international cooperation.

Mark’s beloved wife Mariam, a biochemist at the Rockefeller Institute (see earlier blog posts), had died in January 1920, a victim of the worldwide flu epidemic. Their young son, Edgar, was just two and a half years old. Mark had help with child care from relatives in New York City, but a year later, he decided that Edgar would be better off living with his aunt, uncle, and cousins on the farm in Lebanon, Connecticut, that he had bought in 1919 with his brother-in-law Moisie Vinograd. Mark commuted by train, spending weekends with his son at the farm and continuing to work as a writer and editor in New York City during the week. Life on the farm will be the subject of an upcoming blog post.

Sometime after 1930, when Edgar was a young teenager, Mark Villchur remarried. Tatiana Pavlovna—the “ovna” is the feminine form of the Russian patronymic, meaning her father’s name was Pavel or Pol—was a dentist in her native country, but did not pursue her career after she emigrated. By the time of their marriage, Mark and Edgar had moved back to New York City, but the family continued to spend weekends and vacations at the farm.

The 1930 census shows Mark and Edgar living in the Bronx along with Mark’s niece Fannye, age twenty-eight, a teacher in public schools, and her sister Celia, age twenty-three, a librarian in the public library. Ten years later, the census shows Mark, Tatiana, and Edgar living in Manhattan, at 168 West 143rd Street. Tania, as she was known, was a loving stepmother to Edgar through his teen years and young adulthood. She worked at the Common Council for American Unity alongside her husband.

That census was taken on April 1, 1940. Two months later, Mark Efimovitch Villchur died of a heart attack at the young age of fifty-six. My grandmother Tatiana (Tania) preserved all the many telegrams, notes, and letters of condolence, as well as several articles and obituaries in English, Russian, and Ukrainian. Mark was remembered as a kind-hearted, generous soul who helped those in need. One obituary says in Russian, “He was very popular and famous among Russian immigrants. For the last fifteen years he was the head of the Russian Bureau of the Foreign Language Service Newspaper. He helped many immigrants become citizens.” The wife of the engineer on the SS Normandy wrote, also in Russian: “He was a good person, I visited their home, and he was very hospitable. He helped me become a citizen and I am grateful for that. I keep his memory in my heart.” There were numerous expressions of shock and sadness from friends and colleagues at the Foreign Language Information Service. Several of Tatiana’s relatives wrote from California asking her to move out to the West Coast to live with them, which, in fact, she did. Edgar, then twenty-three years old and employed as a commercial artist, decided to remain in New York.

Although she lived across the country from her stepson and his family, Tania Villchur kept in touch through hand-written letters. I visited her several times at her home in Los Angeles. My father supported her throughout her life, and would see her whenever he went to audio shows in California with his company, Acoustic Research. She died in 1982.

My father had no memories of his mother, although he kept all her papers and many photographs. He remembered his father as an accomplished writer and a dedicated advocate for the rights of immigrants and minorities. When he spoke of his father, Edgar often mentioned how grateful he was to be an American. He had escaped the anti-Semitic repression of tsarist Russia, and had survived the deadly pogroms. His adopted country gave immigrants from around the world the opportunity to become citizens, the right to vote, and the ability to retain the traditions of their native lands even as they were becoming part of the American fabric.

But of all the freedoms he had been given, Mark Efimovitch Villchur told his son that the most amazing one was the freedom to travel around without having to tell anyone where you were going, and without fear of being stopped and asked for papers. Mark told Edgar that he must always treasure this freedom, and must always work to ensure that America remains a place where people had the right to move freely from place to place.