The Villchur Blog posts articles about the life and career of author, educator, and inventor Edgar Villchur. This is the third article about Villchur’s experiences in World War II.

By Miriam Villchur Berg

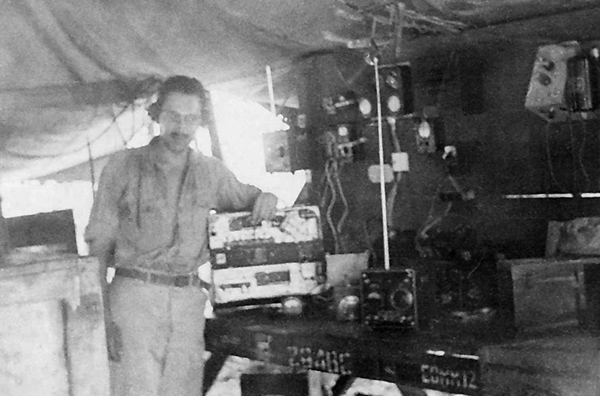

Villchur made several “Unsatisfactory” reports concerning radio equipment on the P-47 fighter planes while he served as the Communications Officer of his unit. The first was a report on a capacitor that tended to break down suddenly during flight, causing complete failure of the radio receiver and rendering impossible any communication between the pilot and ground control or other aircraft. He discussed the problem with the Communications Officers at the other squadrons in his area, and discovered that each of them had experienced up to fifteen radio failures in a six-month period, all due to this defective part. The fix was simply to replace the capacitor, but Villchur went on to recommend that the manufacturers be told to perform more rigorous inspections of these radio parts to make sure that they were meeting the electrical specifications called for by the Army Air Corps requisitions.

His second “Unsatisfactory” report gave rise to a favorite story that Villchur told friends and family in later years. Airplanes were losing radio reception about fifty miles out from base, when they should have had a much greater range. Villchur, who was not a pilot, had no way to observe the problem first hand, so a pilot offered to take him up in the P-47 to see for himself. The P-47 Thunderbolt is a one-person aircraft, but Villchur, who was five foot nine and one hundred and sixty-five pounds, managed to squeeze himself in under the panel with the pilot. Hearing how the radio signal cut in and out convinced him that the problem was in one of the vacuum tubes.

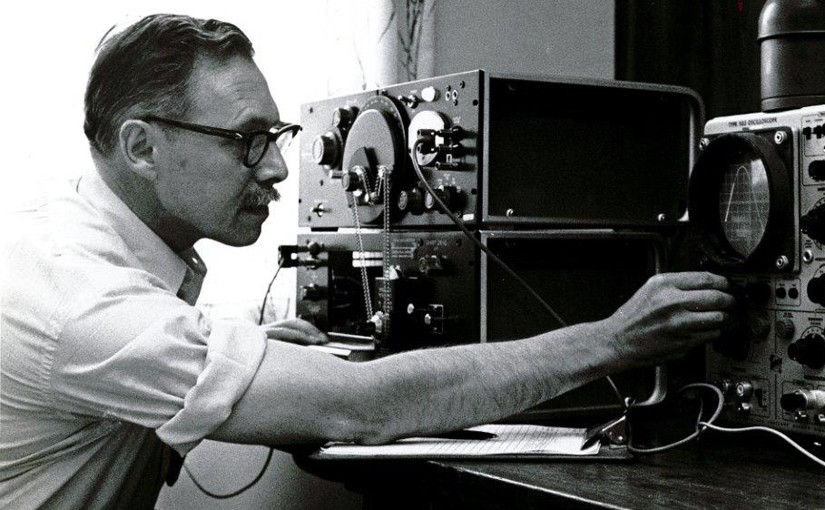

On returning to base, Villchur tested the tubes in the plane, and found inconsistencies in one of them, the VT-132. He checked all the VT-132 vacuum tubes in stock, looking for defective ones. Without laboratory equipment, he had to invent a system for testing. In his report, he writes: “A controlled check was made of 200 tubes taken from unbroken cartons and selected at random from the shelves of a signal service company…. The receiver was allowed to warm up for thirty minutes to secure stability…. As a check on the constancy of the signal strength and any other affecting conditions, the original VT-132 used in the receiver was substituted after every five tubes were checked…. It is the experience of this section that the greatest factor making for inadequate receiver sensitivity, including that of receivers in new planes sent to this organization, is defective VT-132’s…. It is recommended that the inspection of VT-132’s be made more rigid and the required standard for overall efficiency be raised.”

The report was forwarded up the chain of command, and resulted in a new policy, giving the vacuum tubes an operational check before the Signal Corps would accept them. The Chief of the Communications Maintenance Section added a note: “This report, by virtue of its excellent preparation, will be very effective in expediting corrective action.”

During his time as Communications Officer, he also devised a method of testing radios without removing them from the airplanes, saving time and effort.

One day, Villchur was reprimanded by a superior officer because one of his men had left a tool kit out in the rain. Villchur said he would take care of it. The next day he was summoned to the Commanding Officer’s office. When he got there, his squadron CO, the squadron communications officer, and the Group Communications Officer (a group consisted of several squadrons) were all there.

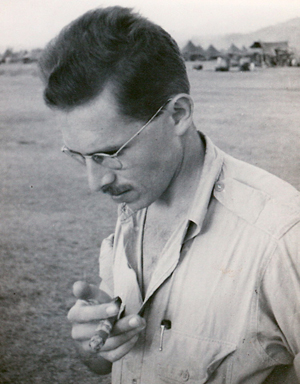

In telling this story to family and friends later in life, he remembered how he had assumed he was going to be punished for leaving the toolbox out in the rain—and he couldn’t believe they were making such a big deal about this little mistake. So he was very surprised when, instead of a reprimand, he was given a Citation of Appreciation for Meritorious Achievement, based on the vacuum tube report he had submitted six months earlier and the in-plane testing system he had devised. His Army superiors had read his reports and decided to change procedures.

Shortly after that, Villchur was promoted to Captain and awarded the Bronze Star, the fifth highest medal given by the US military, awarded for meritorious service in a combat zone. When he told the story years later, he rarely mentioned the medal he received. What made him most proud was the fact that he had figured out what the problem was and made a recommendation as to how it could be remedied. He was surprised that his superior officers had paid attention to his report, and it gave him great satisfaction that they actually changed procedures for testing the vacuum tubes. Because of his careful and detailed report, airplane radios did not fail, and pilots were able to stay in communication with their ground crews. And even though Villchur disdained the Army’s non-egalitarian system of hierarchy and ranks and medals, it didn’t hurt that he received recognition for his efforts—a citation, a promotion, and the Bronze Star.

Edgar Villchur was twenty-six years old when he put in his vacuum tube report. His education had consisted of a master’s degree in art education and field training in radio repair from the US Army Air Corps. But he had already figured out how to do original scientific research, how to address and solve specific problems, how to write up his work in a way that would be understood, and how to make a recommendation that would be listened to. The military bureaucracy is often accused of being resistant to changes in procedures. Villchur found a way through that resistance, and effected a change in policy that made the airways safer for American pilots.

© Miriam Villchur Berg