The Villchur Blog posts articles about the life and career of author, educator, and inventor Edgar Villchur.

Edgar Villchur served in the Army Air Corps for four years during World War II, including twenty-eight months in the South Pacific. His unit moved several times, each time setting up camp closer to Japan. Starting from New Guinea in June of 1943, the 348th Fighter Group moved every few months, to several locations in the Philippines and finally to Ie Shima, an island near Okinawa, in July of 1945. One month later, Japan surrendered, and the war was over. The camp was closed on August 31, 1945.

Edgar had been corresponding regularly with his girlfriend Romy back in the states. He had painted her name (Rosemary) on the front of his Army jeep, and sent most of his Army pay home to her. Romy’s conservative Presbyterian parents were a little apprehensive about their daughter’s arty Jewish beau, but they soon accepted him, and two months after he got home, Edgar Villchur married Rosemary Shafer in a simple ceremony at Romy’s parents’ home in Staten Island. Eddie wore his dress uniform, and Romy wore an elegant light green dress.

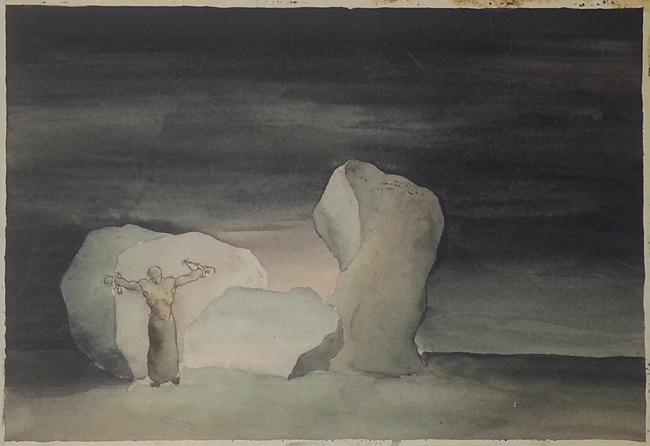

They set up housekeeping in Greenwich Village, and Eddie started looking for work. In college he had been an art history major, and had received an M.S. in education, so he was qualified to teach art and art history. Eddie had done theatrical set design, including a set for Prometheus Bound, a play by the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, in an off-Broadway production. During college, he had also spent summers as a camp counselor, running the dramatics program for the campers. He knew about many aspects of theatrical production—lighting, props, sound, and all the behind-the-scenes details.

Villchur went to visit his City College art history professor, Albert d’Andrea, and asked for guidance. Professor d’Andrea was very candid with Eddie. He said there were very few jobs in the world of theatrical production. He asked Eddie what he had learned during the war, and Eddie told him he had learned to fix radios. Professor d’Andrea advised him to use that, and said that people were depending more and more on their radios and phonographs for entertainment.

The radio had become an essential part of American life. Starting in the 1930s, families spent many evenings in their living rooms, gathered around furniture-sized radio consoles, listening to news, sports, comedy series, dramas, and music. Edgar and his family had for many years enjoyed Metropolitan Opera radio broadcasts and other classical music programs such as The Voice of Firestone and The Bell Telephone Hour.

Edgar loved jazz and big band music as well, and listened to the Make-Believe Ballroom regularly. New York’s radio station WNEW started broadcasting the Ballroom in 1935, with Martin Block announcing as if he were a disc jockey at an actual ballroom. Martin Block invented the genre of the radio DJ show. When he started, WNEW had no records other than those Block bought. The station’s management, and most radio broadcasters, thought that the radio audience wanted live music played over the airwaves. They did not believe that advertisers would pay for airtime on an all-recorded-music radio show. Block found his own sponsors, and was enormously successful. In one famous incident, he advertised a sale on refrigerators during a New York City snowstorm, and more than one hundred people slogged through the snow to take advantage of the bargain. After that, advertisers lined up, and the radio station had to keep a waiting list for sponsorship spots on the show.

Block played popular dance tunes by big bands such as those headed by Count Basie, Harry James, and Gene Krupa. One of Villchur’s favorite jazz performances was “Sing, Sing, Sing” by Benny Goodman, with solos by trumpeter Harry James, drummer Gene Krupa, and the bandleader himself on clarinet. On Saturday nights, Block hosted the “Saturday Night in Harlem” segment, introducing America to the music of the great black jazz masters—Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Billie Holliday, and others. These were some of Eddie’s favorite performers.

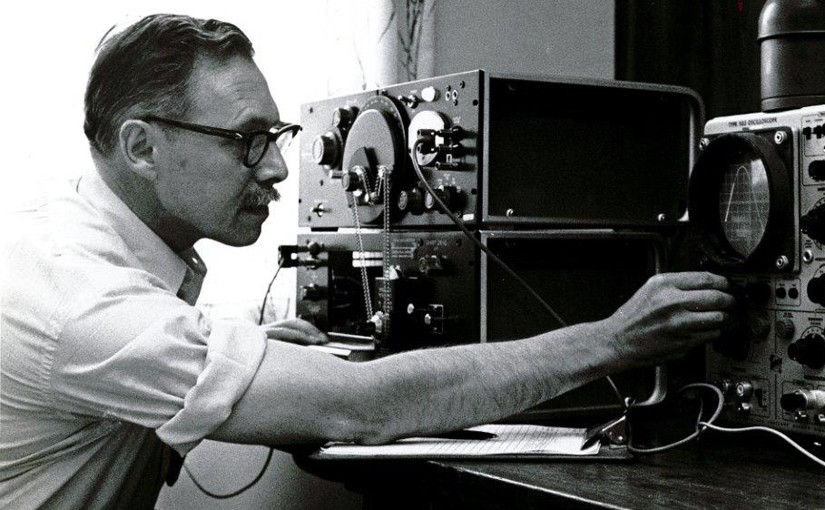

Radio continued to hold a central place in American family entertainment after the war. So Villchur decided Professor d’Andrea was right, and that it made sense for him to use his army training to work in radio repair. He put some of the money he had saved during his time as a soldier and invested it in renting and outfitting a radio repair shop on West Fourth Street in Greenwich Village. In addition to radio repair, Villchur built custom sound systems for customers. One of those customers was Abe Hoffman, a friend who later became the chief financial officer of Villchur’s loudspeaker company, Acoustic Research, Inc. In a memoir he wrote in 2005, Hoffman described the system Villchur installed in his apartment in Manhattan:

“I had known Edgar and his wife, Romy, and had visited with them in their Greenwich Village apartment some years before. Also, he had created a one-piece sound reproduction system for me. It consisted of a Jensen speaker, a Meissner tuner, a Garrard turntable and cartridge, and a Villchur-built amplifier. It was housed in a solid walnut cabinet and cost six hundred and twelve dollars including two-percent sales tax. It served me well for that time. I played a lot of Peter and the Wolf for my young son Fred as well as other fine music.”

The Villchurs put the rest of their savings into buying a home. Along with two other couples, they purchased a brownstone at 404 West Twentieth Street in the Chelsea district of Manhattan. It was a historical building—the oldest townhouse in Chelsea, built in 1900 by Clement Moore, the poet who wrote “A Visit from Saint Nicholas” (popularly known by its first line, “’Twas the Night Before Christmas.”) Romy and Eddie had the bottom floor, and the other couples had the second and third floors. (I looked it up online, and found that it was in fact for sale in September 2015. It is in need of extensive repair, so it is a fixer-upper, bargain-priced at $6.5 million. In 1947, the Villchurs and their friends paid a total of $6,000 for it, or about $60,000 in today’s dollars.)

Unlike the proverbial cobbler whose children go shoeless, Villchur used his talents to build sound systems for his family, including a phonograph, amplifier, radio tuner, and speaker for the living room. (He also built a small personal set for me, with a bright blue, painted speaker cabinet. My mother found the perfect fabric for the grille cloth. It was a small print with rows of pedestrians on a tree-lined street—not unlike the street on which we lived. I remember listening to Burl Ives singing “The Little White Duck, and “Mr. Froggie Went A-Courtin’” and looking at the tiny pictures of people walking up and down the street, pushing their baby carriages, and greeting their neighbors. It was a perfect little world.)

Edgar’s radio shop prospered. Being an entrepreneur allowed him the freedom to pursue more education in his new field of endeavor. He spent hours in the New York Public Library on Fifth Avenue, reading all the books he could find on physics and higher mathematics, as well as works on the applied sciences such as audio engineering and sound reproduction. He also started writing articles and submitting them to both technical and general publications. His clear explanations of complex ideas won favor with editors, and he started getting regular writing jobs. Audio Engineering magazine (later renamed Audio) contracted with him for an article each month. He also wrote on more general topics for Saturday Review, edited by Norman Cousins, a well-known activist for nuclear disarmament and world peace.

Edgar made an appointment with the administrators of the night school at New York University, armed with several of his published articles and an outline for a proposed course on sound reproduction. Villchur emphasized his master’s degree in education (and may have downplayed the fact that his major was art history). He was persuasive, he was articulate, he could write and think clearly, and he was offering a course that was of great interest to many students at the time. NYU hired Villchur to teach the course that he designed, entitled “Reproduction of Sound,” one night a week at their campus off Washington Square in Greenwich Village.

In 1951, the Villchurs moved to a residential area in Queens. It offered more outdoor space and less noise than Manhattan, but the family was not happy with the suburban environment. With a fairly regular career in writing and teaching, Villchur realized the family didn’t have to live in the city. He could write from anywhere, and could travel into New York once a week to teach. Eddie had lived in the country as a boy, and had loved it. Romy had grown up in Staten Island, on a property with many trees, a terraced lawn, and gardens. So they started looking for a place to move. Romy saw an ad in Saturday Review for a place for rent in Woodstock, New York. Eddie had heard of the town because the Art Students’ League, a famous New York City art school, had a summer campus there. So the Villchurs made an appointment with a real estate agent, and drove two hours up the Taconic Parkway (the section of the New York State Thruway between New York City and Kingston was not opened until 1954).

The house that had been advertised wasn’t to their liking, but the agent showed them a few other places, including the home of Gene and Hannah Ludens on Chestnut Hill Road in the hamlet of Zena. The whole family fell in love with the house, and the Villchurs and Ludenses got along famously. Gene was a painter, and Hannah was a sculptor. They spent their summers in Woodstock, and traveled to the Midwest each fall to teach art at the University of Iowa. This was the first time they were planning to rent out their house for the whole year, and they wanted to make sure it went to responsible people. When they met the Villchurs, the Ludenses knew they would take good care of the house. The rent was $60 a month.

For the next few years, Eddie wrote his articles in his loft office above the living room. The publishers required a specific number of words, so he would write the articles out longhand, count the words, and adjust as needed before typing the manuscript. (I remember many times coming home from school and hearing my mother say, “We have to be quiet. Papa is counting words.” As I sit here typing this blog post, the number of words in the document appears instantaneously and continuously on the bar at the bottom of the screen.)

Edgar Villchur, in his usual organized and methodical way, set up the life he wanted. He educated himself in his chosen areas of interest. He convinced a prestigious university to hire him to teach a course he himself had invented, using a curriculum he had written. He found a way to support himself and his family and to live in a cozy home in a rural and artistic community.

The scene was set. In the next year, Edgar’s field experience in radio and sound systems, combined with his self-education in physics and engineering theory, would come together in a moment of revelation. But that is a story for next time.

© Miriam Villchur Berg