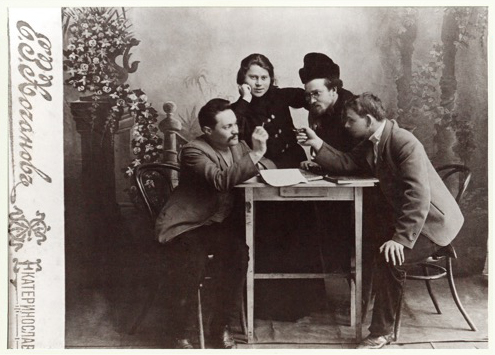

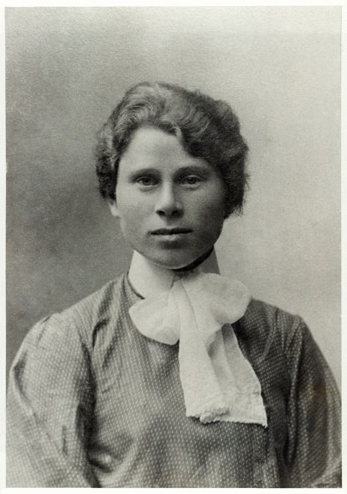

Mariam’s brother Moisie, his wife Rachaeleah, and their three children had emigrated and were living in New York City. Her fiancé, Mark Efimovitch Villchur, had left for New York around 1911. But Mariam decided to postpone her emigration, and applied to school in Germany. She had to leave her sister Lisa and her brother Robert behind in Russia. She posed for pictures with friends and relatives, including her sister, before leaving the country.

I was surprised to learn that Germany was more open to educating women and Jews than Russia was at the turn of the twentieth century. Although anti-Semitic sentiments and activities can be found in all periods of German history, the last half of the nineteenth century saw a lessening of such policies. Jews were “emancipated” (that is, given nearly full rights as citizens and no longer forced to live in restricted areas) under the unification of Germany in 1871. Efforts by anti-Semitic groups to rescind Jewish emancipation did not receive a majority of votes in the new German parliament. By 1910, the Jewish population in Germany numbered over 500,000. Jews from neighboring countries took advantage of this newfound freedom—nearly 80,000 came into Germany from Russia.

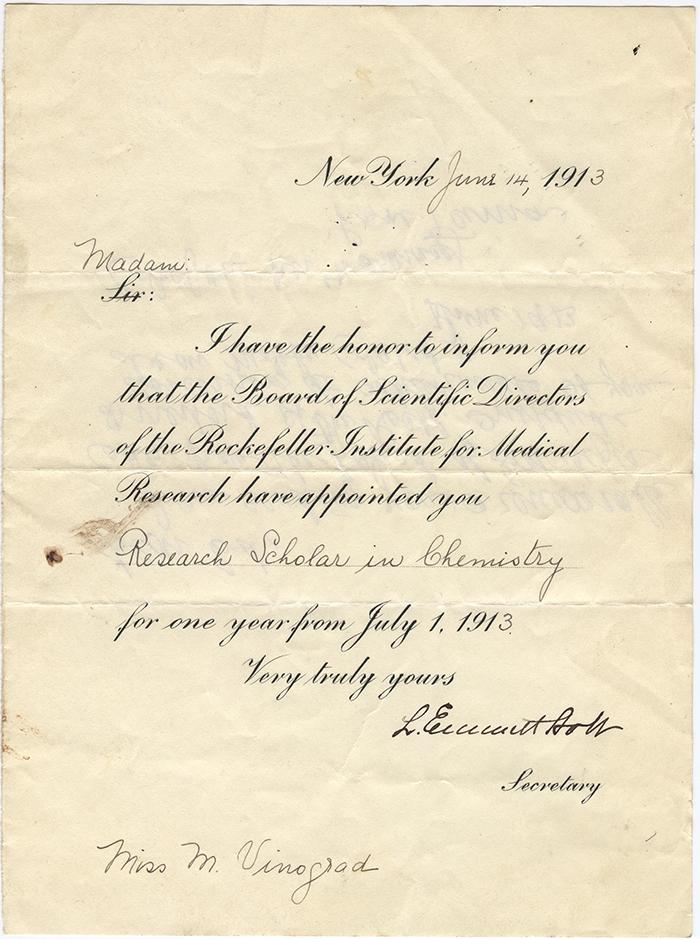

After Mariam completed her doctoral degree, she crossed the ocean and joined her fiancé, Mark Efimovitch Villchur, in New York. Mark had landed a great job, working as the city editor of the largest Russian-language daily newspaper in New York City (more on him in upcoming blog posts). Mariam applied for and received an appointment to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York City. Her letter of appointment, a printed form letter with the particulars filled in by hand, shows the salutation “Sir”—this has been carefully crossed out and replaced with the handwritten “Madam” above it. Although she was not the only female scientist at the Institute, the forms had not caught up with that fact. The letter of appointment is dated June 14, 1913:

In the late nineteenth century, women from numerous countries were making major accomplishments in the field of chemistry. Louise Hammarström and Anna Sundström were working in Sweden. In Russia, Anna Volkova, Nadezhda Olimpievna Ziber-Shumova, Julia Lermontova, and Vera Popova were doing important work. (It’s worth noting that none of these Russian women were Jewish). Agnes Pockels was working in Germany, and in the United States Ellen Swallow Richards and Mary Engle Pennington were making contributions to the field.

Most of these women are footnotes to history, remembered for being the first of their gender to receive post-graduate degrees or other distinctions, but some also have interesting stories or specific accomplishments. Agnes Pockels learned science from her brother’s textbooks, and invented a method of measuring surface tension using a device now known as the Pockels trough. The brilliant but unlucky Vera Popova married a Russian general on the condition that he build her a laboratory. She died in an explosion in that lab, trying to synthesize hydrogen cyanide.

Mariam Vinograd also did investigative work on arsenic. Her first published scientific article, “Determination of Arsenic in Organic Matter,” was published by the Journal of the American Chemical Society (Vol. XXXVI, No. 7, July 1914) and reprinted as a monograph by the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research. Since this work came so shortly after her appointment to the Institute, we can speculate that it was gleaned from her recently completed doctoral thesis. The study deals with methods of discerning the amount of arsenic in organic substances, and includes a systematic review of known methods along with detailed instructions for the most accurate methods using state-of-the-art laboratory equipment. One cannot help but wonder whether Mariam studied the work done by Ellen Swallow Richards on testing for arsenic.

Although we now think of arsenic as a poison to be avoided under all circumstances, in the early twentieth century it was thought of as a substance with both helpful and harmful characteristics. An arsenic compound named arsphenamine was synthesized in 1907 and marketed as Salvarsan. It was the first treatment for syphilis that did not depend on mercury (which was even more toxic). Mariam mentions Salvarsan in her article: the process she describes includes introducing Salvarsan in known quantities into test samples of tissue or blood in order to evaluate the accuracy of the various methods of arsenic testing.

Another arsenic compound, Tryparsamide, was developed within the same decade, and became the first known cure for Trypanosomiasis, or African sleeping sickness. In 1920, the Rockefeller Institute sent another female scientist, Louise Pearce, to the Belgian Congo (now Democratic Republic of the Congo) to test that drug on patients. The results were highly encouraging—an 80 percent success rate—but high doses caused partial or total blindness, so its use had to be discontinued.

What we think of as poisons can sometimes have therapeutic value. Likewise, every substance we think of as beneficial—even oxygen, water, or sunlight—can cause injury or death if the dose is too high. The modern-day saying “the difference between medicine and poison is dosage” comes from Paracelsus, a sixteenth-century Swiss scientist whose teachings were undoubtedly studied by Mariam Vinograd.

A contemporary of Leonardo da Vinci, Copernicus, and Martin Luther, Paracelsus (who was also an alchemist, an astrologer, and a military surgeon) is considered the father of toxicology. He said, “All things are poison and nothing is without poison; only the dose makes a thing not a poison.” In treating soldiers wounded in battle, he abandoned the common practice of wrapping wounds in cow dung in favor of keeping them clean. He wrote, “If you prevent infection, Nature will heal the wound all by herself.”

Paracelsus was also the first to give lectures in the vernacular German rather than the usual Latin, since he wanted to impart medical and scientific knowledge to as many people as possible. This and other medical heresies (he wrote, “What else is the help of medicine than love?”) incurred the wrath of the medical establishment, and he found it difficult to get his writings published. In addition, the Roman Catholic Church frowned on his teachings, in part because of his belief that the universe was one coherent organism with a unifying spirit, and that this—the spirit of the planet and all beings on it—was the definition of “God.” He wrote, “In us there is the Light of Nature, and that Light is God.”

Mariam Vinograd’s research on arsenic was done in the light of Paracelsus and his pioneering work in toxicology. Her work enabled later discoveries of better medicines for deadly diseases. Mariam must have felt a kinship with the small group of women who were undaunted by the obstacles placed before aspiring female scientists, and who took their place among the scholars and researchers of the age. Her article on arsenic is written in excellent English, and all of the references are from German research studies. She apparently spoke and read fluent German, English, and Russian, and may have also known Ukrainian, Yiddish, and Hebrew.

In the next blog post, we will follow her career at the Rockefeller Institute and the remainder of her tragically short life.