Mariam Vinograd, Edgar Villchur’s mother, applied for and received an appointment as a research scholar at the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research shortly after arriving in New York around 1912. It was an excellent job, with opportunities for original research that could make a difference in the world. And the Institute was well funded, thanks to its founder and benefactor, John D. Rockefeller.

John D. Rockefeller (1839-1937) founded Standard Oil (later named Esso—a spelling out of the company’s initials, S.O.—and then Exxon). As the importance of gas and oil grew, so did Rockefeller’s wealth. During his lifetime he was the richest man in the world, and he is considered by many to be the wealthiest American of all time. He was the first person in history to be worth more than a billion dollars (more than twenty-four billion in today’s dollars).

Although Rockefeller was criticized for unscrupulous business practices by muckraking journalists such as Ida Tarbell, many who knew his work have written that his business dealings were humane, especially when compared with his contemporary Andrew Carnegie. Rockefeller was a deeply religious man, and charity was an essential part of his faith. Even as a sixteen-year-old, in his first job as a clerk, he gave six percent of his earnings to charity. He belonged to the Northern Baptist Church, but when he traveled in the south, he often attended services at African-American Southern Baptist churches, and would always leave a substantial donation.

After retiring in 1897, he devoted his life to philanthropy. He founded the University of Chicago and turned a small volunteer-run Baptist seminary into Spelman College (one of the earliest colleges for African-American women). He provided major funding to many other educational facilities. When his grandson died of scarlet fever in 1901, Rockefeller decided to fund a research facility dedicated to curing and eradicating the infectious diseases of the world. He donated hundreds of millions of dollars to establish and operate the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research and its adjunct hospital. In 1965, that organization added graduate education to its purview and became The Rockefeller University. Since its inception, the Rockefeller Institute and University have provided laboratory and study facilities to scientists—twenty-three of them Nobel prize laureates—who have made major advancements to the fields of genetics, infectious disease, public health, and the study of medicine. In its certificate of incorporation, the purpose of the Rockefeller Institute is given as “medical research with special reference to the prevention and treatment of diseases.”

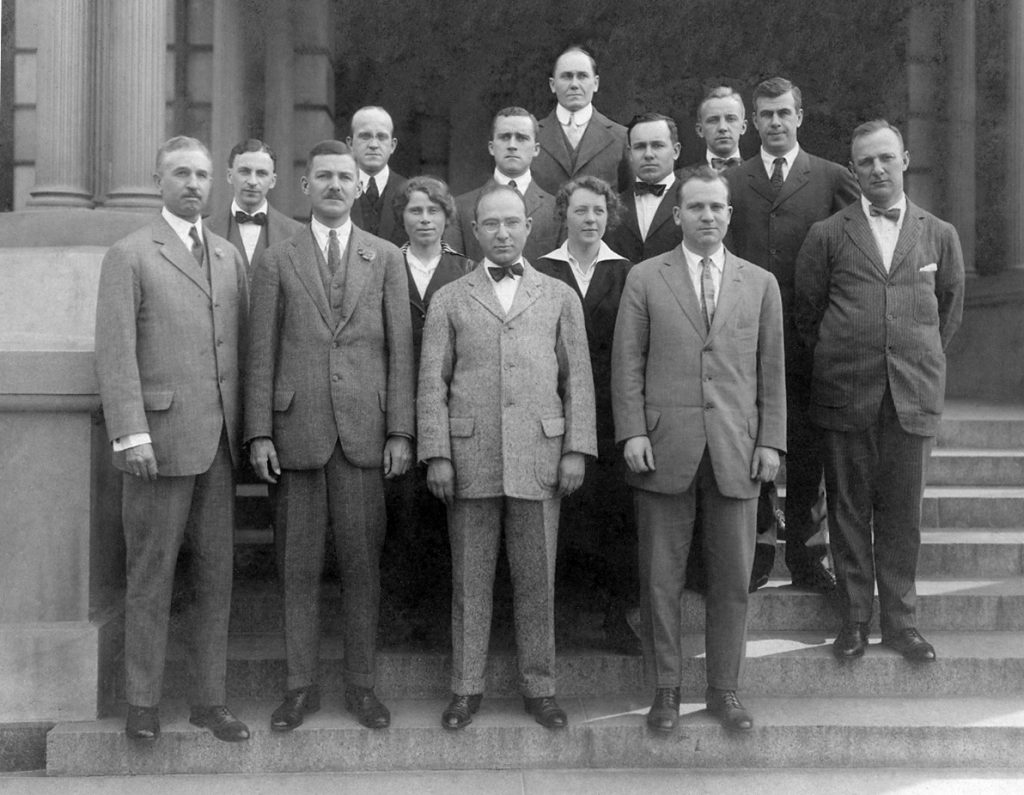

The Institute encouraged women to become scientists. Photographs from the era show several women among the men on the research teams. The report of the Director of Laboratories for January 1915 shows that research was being conducted on polio, dysentery, influenza, mumps, streptococcus, beriberi, and pneumococcus. The volume for the next period adds meningitis, typhoid, rheumatoid arthritis, cancer, and trypanosomiasis. This last disease, also known as sleeping sickness, killed two-hundred and fifty thousand people in Uganda on the lower Congo River in 1901. Two years later, Scottish physician and microbiologist David Bruce identified the vector for the disease as the tsetse fly. In 1910, Nobel laureate bacteriologist Paul Ehrlich, of gram-staining fame (no relation to Paul R. Ehrlich, who wrote The Population Bomb), developed an effective treatment based on arsenic. Although it cured eighty percent of cases, it had to be abandoned when it was found to cause permanent blindness in many of the patients. As Paracelsus said, the dose makes the poison.

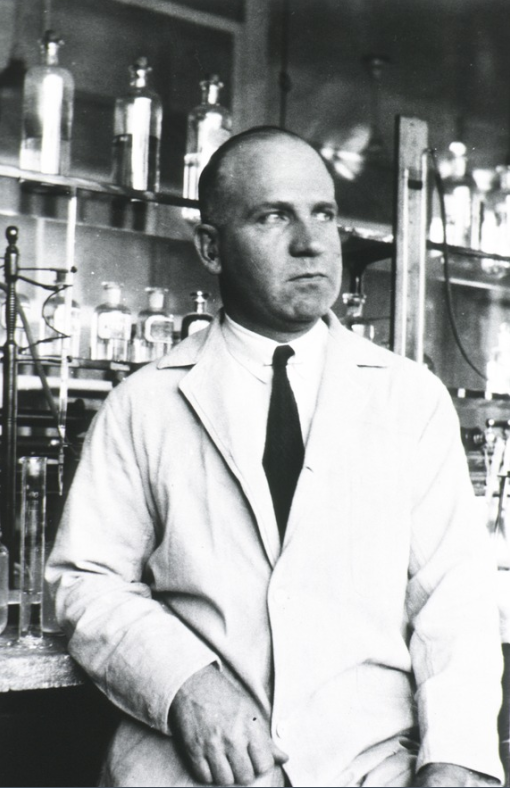

Mariam Vinograd was apparently heavily involved in research on arsenic, probably in hopes of finding a way to make it safer as a treatment for various diseases. A research paper by her (which may have been excerpted from her doctoral thesis) was accepted by the Journal of the American Chemical Society (Vinograd, Mariam. “Determination of arsenic in organic matter,” JACS Vol, 1914, xxxvi. 1548, xxii., 372.), and then printed as a monograph by the Rockefeller Institute. She joined the Rockefeller chemistry research team led by Donald D. Van Slyke.

It was common practice for the Rockefeller Institute to send its fellows abroad for additional work, and in 1911 Van Slyke was sent to Berlin to study at the Kaiser Wilhelm Society under Nobel laureate Emil Fischer. I was unable to discover at which German university Mariam studied, but it may well have been in Berlin; it is entirely possible that Van Slyke met Mariam Vinograd in Berlin during that year, and that his familiarity with her work paved the way for her to be hired as a research scholar at the Rockefeller Institute in New York City two years later.

In addition to the paper on arsenic for which she is the sole author, Mariam is listed as an additional author on three other scientific journal articles. One of these was the study that disproved the validity of the pregnancy test invented by Emil Abderhalden. She and her research team used the test on three groups: women who were pregnant; women who were known not to be pregnant (because they were too young or too old, or because they had just given birth); and men. In the summary, the scientists conclude, “The individual variations of both pregnant and non-pregnant sera make the results from both overlap so completely as to render the reaction, even with quantitative technique, absolutely indecisive for either positive or negative diagnosis of pregnancy.”

On the Wikipedia page for Emil Abderhalden, it says that he is known for developing a blood test for pregnancy, but that it was determined to be unreliable a few years after its inception. The footnote to that sentence references Donald Van Slyke and Mariam Vinograd-Villchur as authors of the article disproving Abderhalden’s work.

It’s worth noting that Abderhalden went on to become a Nazi sympathizer, and helped purge Jews from the German Academy of Natural Scientists. Although Abderhalden did not participate directly, his work was used by Josef Mengele, the physician in charge of selecting prisoners for medical experimentation, forced labor, and death in the gas chambers at the Auschwitz concentration camp. Mengele was trying to develop a blood test for identifying Aryan and non-Aryan individuals, and (mistakenly) thought that Abderhalden’s research could create such a test.

Edgar Marion Villchur was born on May 28, 1917. His mother preserved details of his first year in a satin-bound baby book. We can tell a lot about his mother by reading what she wrote in that baby book. She wanted to preserve every moment, every detail of his early life. Being the scientist she was, she carefully recorded his weight: weekly for the first six months of his life, and monthly after that until he was almost a year and a half old. Mariam’s work in the laboratory had always been in metric units, but she recorded Edgar’s data in the “proper” American way, in pounds and ounces.

Mariam gives tidbits of information that paint a picture of Edgar’s babyhood: his hair was almost white at birth, and then golden brown (in later life, it was dark brown); he liked to go to the park; he was punished for breaking flowers off houseplants at the age of one year, eight months; his dog Grushka almost knocked him down when he took his first step; and he recited his first poem in Russian on his second birthday.

When I read about the poem, I immediately knew which poem she was referring to. Even in his later years, he talked about how he recited that poem when he was two. It’s a nursery rhyme that everyone in Russia knows by heart. It tells the story of a rabbit who goes for a walk and gets shot by a hunter. “Oh no! My rabbit is going to die!” But then the rabbit comes home, and he is alive. The lines Edgar remembered from age two until age ninety-four, and that he would recite with great solemnity, are:

Pif-paf oy oy oy!

Umiraet zaichik moy.

Then he would, with the same solemnity, translate:

Pif-paf oy oy oy! (this “translation” always got a laugh)

My little rabbit is going to die.

Edgar knew a few words in Russian even in his nineties, but his fluency apparently did not survive past his early childhood.

The page in the baby book on which baptisms, christenings, and such are recorded best demonstrates what an independent and free-thinking woman Edgar’s mother was. That page reads, “Religious Ceremonies.” Mariam’s entry reads, “None. We want your religion to be Justice, Truth, Fearlessness, and Righteousness.”

On the page for “Baby’s First Party,” Mariam lists eleven friends and relatives who came to celebrate Edgar’s first birthday. She recounts that he received “gifts of clothing and very fine toys.” Then she adds that Dr. and Mrs. Van Slyke came by to visit the next day. It must have been gratifying to her that her supervisor from the Rockefeller Institute came to pay his respects. It increases my confidence that she knew Dr. Van Slyke in Berlin, that he thought of her as a friend as well as a colleague, and that he helped her obtain the position at Rockefeller. It also means that he was not angry that she had left the laboratory.

Unfortunately, this seemingly idyllic family life did not last long.

The influenza pandemic of 1918 was one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history, killing fifty to one-hundred million people—three to five percent of the world’s population. The flu was deadlier than the Black Death in the fourteenth century, and killed more people in twenty-four weeks than the AIDS epidemic killed in twenty-four years. Unlike many epidemics, its victims were mostly healthy young adults, because it caused overstimulation of their strong immune systems.

One of those victims was Mariam Vinograd-Villchur, Edgar’s mother. Although most of the deaths occurred in the first year of the flu, Edgar’s mother succumbed later, dying on January 31, 1920. She was thirty-four years old, and her son was two years, eight months old.

Ironically, it was a Rockefeller scientist, Richard Shope, who isolated and identified the virus that caused the deadly influenza epidemic. His work was published in 1928, eight years after the death of Edgar’s mother.

Edgar’s father was fortunate to have relatives to help care for his two-year-old son. As you will read in the next blog post, he had bought a one-half interest in a farm in Connecticut along with his wife’s brother Moisie. It was there he decided to move with Edgar, leaving him in the care of his cousins, aunt, and uncle during the week, while his father commuted to New York City to work. But more about that later.

Author’s notes: I am very grateful to the Rockefeller University Archives for their invaluable help in identifying Mariam Vinograd-Villchur’s positions and work projects in that organization.

Scientific articles authored or co-authored by Mariam Vinograd-Villchur

Osborne, T. B., Van Slyke, D. D., Leavenworth, C. S., and Vinograd, M., “Some products of hydrolysis of gliadin, lact-albumin, and the protein of the rice kernel.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1915, Vol. xxii, No. 2, Sept. 1915.

Van Slyke, Donald D., Vinograd-Villchur, Mariam, and J. R. Losee. “The Abderhalden Reaction.” The Journal of Biological Chemistry, 1915, Vol. xxxiii, Nov. 1915.

Van Slyke, D.D., Losee, J.R., and Vinograd-Villchur, M., “Quantitative test of Abderhalden reaction.” Bulletin of the New York Lying-In Hospital, Vol. x, No. 3, April 1916, reprinted from “A Quantitative Application of the Abderhalden Serum Test,” American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology, Vol. xxiii, No. 2, Feb. 1916.

Vinograd-Villchur, Mariam. “Determination of arsenic in organic matter,” Journal of the American Chemical Society, 1914, Vol. xxxvi, No. 7, July, 1914.)