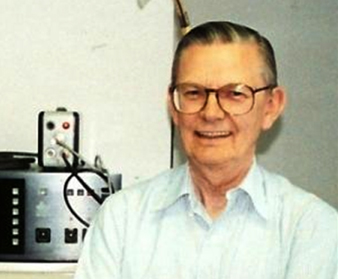

Before continuing with the story of Edgar Villchur and Acoustic Research, I want to pause to remember a great man, Roy Allison, a longtime colleague, collaborator, and friend of Villchur’s who died last month at the age of eighty-eight.

Five years later, when Allison’s contract was up, he left AR and started doing research on his own. He is well-known for working on the “Allison boundary dip,” a phenomenon in which loudspeakers show consistent power response in a testing environment, but become irregular—losing power in the middle of the bass range—when placed into a typical living room. Allison figured out the cause and how to fix it, received patents, and started his own loudspeaker manufacturing company, Allison Acoustics, in 1974.

Villchur was very pleased with Allison’s new products. In a speech to the Acoustical Society of America in June 1997, he said: “No one has imitated the Allison tweeter, a sort of pulsating version of the dome tweeter…. I consider it a significant improvement over my original dome in addressing the same problems I did.” The admiration was mutual. In an email I received from Roy in 2010, he spoke highly of my father’s gift for writing: “Would that everyone had the same appreciation for clear language, which also promotes clear thought. Eddie is a master of the language and a mentor to us all.”

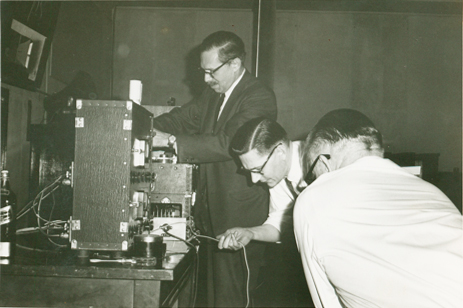

Roy Allison was very involved with the Live vs. Recorded concerts produced by AR, about which I will write later. When the Fine Arts Quartet came to Woodstock in 1959 to record for those concerts, Roy Allison was the engineer in charge. After a long day of taping, the quartet, the engineers, and many Woodstock friends gathered at the Villchur house for dinner and a party. The Fine Arts Quartet was (and remains) among the most important and respected chamber ensembles; I was eleven years old at the time, and an aspiring musician. Awestruck by these musical greats, I felt a little shy. When dinner was announced, Roy Allison, whom I had come to know from audio trade shows, seemed to sense my discomfort. He came over to me and held his arm out, offering to escort me into the dining room and treating me like a grown-up. I felt like a grande dame, and I will never forget his sensitivity and consideration. He was the ultimate gentleman.

To learn more details of Roy Allison’s life, you can read Tom Tyson’s very informative tribute. You can learn more technical details of Allison’s research in “A Glorious Time,” a Stereophile magazine article marking the fiftieth anniversary of the invention of the acoustic suspension loudspeaker. The article contains interviews with both Roy Allison and Edgar Villchur.

— Miriam Villchur Berg