The Villchur Blog posts articles about the life and career of author, educator, and inventor Edgar Villchur. This is the first of three articles about Villchur’s experiences in World War II.

Edgar Villchur was a free thinker and a believer in individual liberty and responsibility. He had no use for things military—the uniforms, the superior and inferior ranks, the blind obedience to orders, and in general the glorification of war and conquest. He was not strictly a pacifist, but rather one who felt that war should be considered a last resort.

World War II, however, was a just war, as far as Villchur was concerned. He served his country for five years, including twenty-eight months in the Pacific theater. He may not have liked the principal of military obedience to authority, but he understood the need for hierarchy and discipline in a wartime environment. When he was drafted in early 1941, the United States was not yet involved in the war. Americans were divided on whether the country should join the war effort. Many felt that neutrality was the best way to ensure our national security. Others deeply regretted our failure to help our allies in the Great War (the United States did not enter World War I until it was nearly over), and felt we should make up for that mistake by allying ourselves with the United Kingdom to fight Nazi Germany. Refugees from Germany were pouring in to the United States with stories of German persecution and violence against Jews, Gypsies, and other non-Aryan ethnic minorities. American isolationists were unconvinced, but among Jewish Americans like Edgar Villchur, there was no doubt that Nazi Germany was on a mission of genocide and needed to be stopped.

The first peacetime draft in United States history was signed into law by President Franklin D. Roosevelt on September 16, 1940. It limited service to twelve months, but was extended in August 1941 as the prospect of war loomed ever larger. Men between the ages of twenty-one and thirty-five were required to register at local draft boards, and were chosen for service by lottery. Many objected to the extension of service, but the issue became moot when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941 and declared war on the United States. The next day, FDR asked Congress to declare war on Japan, and that declaration was passed by both houses within forty minutes. Within a week, Germany had also declared war on the United States, and Congress declared war on Germany and its ally Italy.

Thousands of men and women volunteered for service as soon as the threat to national security was apparent. Once the US entered the war, service was extended to the end of the war, and all men from age eighteen to sixty-five were required to register.

Villchur was called up in the draft lottery in March of 1941, nine months before Pearl Harbor and the US entry into the war. He was part of the 340th Fighter Squadron, which was one of three squadrons in the 348th Fighter Group of the Army Air Corps. This branch of the armed services changed its name over time, becoming the Army Air Force, which was one of the combat arms of the army. After World War II, it was incorporated into the Air Force.

At Fort Dix, on his first day, he learned how to salute and whom to salute. You would be reprimanded if you didn’t salute an officer on the street (but not in a building), and also if you saluted a sergeant, who is not an officer. The enlisted man’s salute is the whole hand, and the most important part of the salute is putting the hand up to the forehead. The officer’s salute is with three fingers, and the important part is briskly removing the hand from the forehead, which is a signal for the soldier to release his salute. Villchur said there was not a lot of attention paid to saluting when they were overseas.

Villchur started training at Mitchel Field near Hempstead on Long Island, and was appointed Technician 5th grade in April of 1942. He decided that the best course of action was to apply for Officers’ Candidate School. He was intelligent and college educated, and entering the war as a trained officer rather than an enlisted man would make it more likely that his skills would be used where they would do the most good. When asked to pick an area of specialization, he chose meteorology, thinking that would be an interesting field and a skill that would be useful to the war effort.

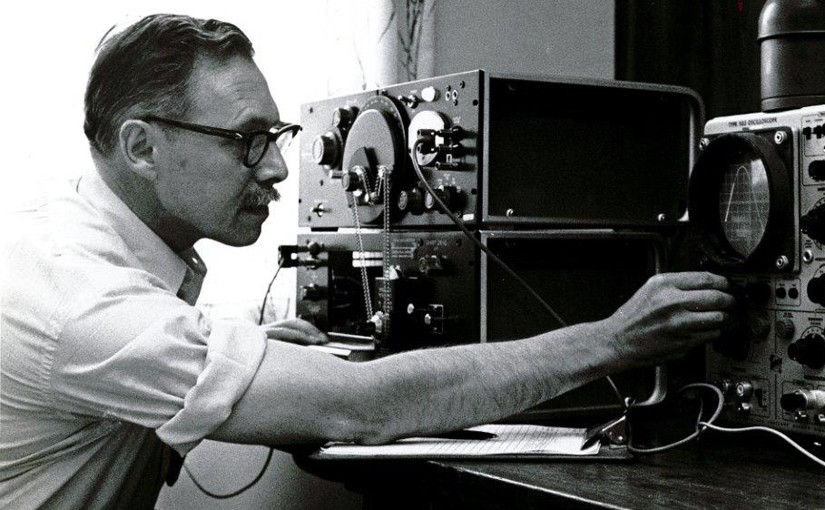

Instead of weather reporting, they assigned Villchur to communications, and send him to Scott Field in Illinois for four months to study engineering and electronics, where he learned to repair and maintain the radios on Army Air Corps airplanes. He was near the top of the class, so they said he had the choice where to go, and he chose New York City. They sent him to LaGuardia Air Field.

He also went to Massachusetts to train on P47s, and his girlfriend (and later wife) Rosemary visited him there. Soon after that he attended Fighter Command School in Orlando, Florida, and took the Communication Officer’s Course, receiving his certificate on October 24, 1942. In May of 1943 he completed the Army Air Force Technical Training at Fort Monmouth Radio School in New Jersey. The 348th Fighter Group was informed that they would soon be sent to North Africa. They marched with full pack several miles to the train station, and boarded the United States Army Transport (USAT) ship Henry Gibbins. They traveled with an escort of four destroyers. Only after they had been on the ship for two days did they receive information about their true destination, the Southwest Pacific arena.

© Miriam Villchur Berg